This article is part of Mixmag’s Cost of Living series exploring how the current economic crisis is impacting dance music. For more features and a list of resources available to UK residents

Making a living as a musician is a precarious business. It’s competitive and difficult to turn into a full-time job, with very few overcoming the odds to get there. And if you manage, a fresh set of challenges around sustaining it as a career are unlocked. Doing it part-time, on top of other income streams or a more traditionally stable job, can be a balancing act that’s taxing on the mind and body. These issues have always been true of the music industry, but conditions are not improving, they’re getting worse.

In 2023, the music industry, already reeling from the impacts of Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic, is now being further squeezed by the ‘cost of living crisis’, which has roots in the both prior issues, as well as geopolitical tensions, corporate greed and associated right-wing politics which prioritise profits over people.

These coalescing circumstances are proving uniquely challenging. Historically the nightlife sector has been thought of as well-suited to weathering times of economic downturn, grouped alongside ‘recession-proof’ so-called ‘sin stocks’ like alcohol and tobacco which people turn to in both good and bad times. “We have seen economic recessions previously and historically the nightclub sector fared relatively well in comparison to other sectors,” notes Tony Rigg, a music industry advisor and lecturer in Music Industry Management at the University of Central Lancashire. In an unpublished academic paper seen by Mixmag, Rigg cites recent research by REKOM UK into the nightclub sector during the 1991 and 2008 recessions which concluded “they were relatively unaffected by the bleak economic context.”

Contemporary evidence on clubbing habits paints an alarming picture. Research published in April 2023 by REKOM UK, which is the UK’s largest nightclub operator, found “over three quarters (77.3%) of Brits say that the cost of living crisis has cut down the number of times they go on a late night out”. Nightlife businesses were the first to close and last to reopen in the pandemic, and alongside their workers are entering this downturn from a significantly weakened position. A 2021 report found that one in three music industry jobs had been lost during the pandemic. After all lockdown restrictions had been lifted, a survey conducted that August found that one third of remaining musicians were still earning nothing, and 83% were unable to find regular work. The pinning of hopes on a post-lockdown boom in going out has not materialised, with clubs and festivals openly struggling. Between the start of the pandemic and the end of 2022, one third of the UK’s nightclubs closed down.

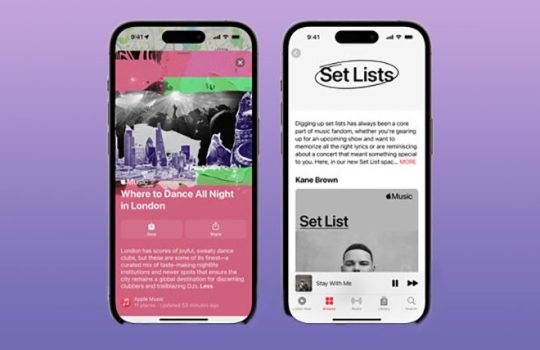

There are wider societal and economic shifts at play here, too. One is the rise of platform capitalism, or what writer James Greig terms as ‘dressing-gown capitalism’, with media subscriptions and delivery apps causing a trend of people favouring staying home in their free time over going out, watching Netflix and ordering a takeaway instead of visiting a cinema, restaurant – or nightclub. The pandemic’s changing of habits and impact on mental health has seen this pre-existing trend gain traction, rather than have the hoped-for inverse response of making previously locked down masses desperate to go out again.

Sof Staune AKA VAJ.Power, a DJ and 3D artist who works a day job programming Glasgow venue Stereo, is conscious of this. “With my circumstances, where I have a stable income, but it also takes up most of my time, I tend to be quite selective with taking on other jobs, as to not take away opportunities from people who really need them,” they say, adding that this allows them to “feel fulfilled and excited about the gigs I do accept, even if it’s for a smaller fee.”

Part-time DJs can generally be more flexible. Manchester’s Clemency has worked full-time since she was 16. “Continuing to work, rather than push for a ‘career’ in music, has always been a conscious decision: I want to play the shows I want to play and I want to make songs when it feels natural, rather than these processes being informed by finances,” she says. But this choice is rarely a privileged decision. “That isn’t to say I don’t need the money I make from DJing and making music,” she adds. “I’m working class, from a single parent family, and I work a low grade admin job in the education sector, so I guess the two depend on each other!” Not everyone has a choice. Sussex-based DJ and GODDEZZ co-founder Kalli holds down a Monday to Friday office job and fits in music where he can. “I live for music, and aspire for it to be my full-time job, but I also have two young sons to support – and music income simply doesn’t provide for bills,” he says

Maintaining a day job is not an infallible shield for protecting creative choices when the cost of living has increased dramatically. “I have also sacrificed a bit of my fussiness for taking shows,” Clemency adds. “Not to say I’m playing loads of stuff I don’t want to, but when the offer comes it’s been harder to say no and I’ve definitely sacrificed energy levels and spending time with friends outside of the scene.” Overexertion and burnout are common. “My day job is quite demanding of the mind, so specific parts of my brain are exhausted by the time I want to start writing music or even to just experiment. My issue is that I want to take on loads more music work but cannot!” says Kalli. “I will work on music when I can late in the evening when I’ve finished work, my sons and partner are asleep and I’ve done all the chores. It takes its toll on me because I have so much to give and so little time and energy to inject back into it all.”

There’s also heightened tensions among peers. In the music industry, the lines between friendship and business can often be blurred, but now firmer boundaries are having to be drawn. “You have to make it make sense for you. You have to stick to your guns and not do as much favours as before,” says Afro house innovator Supa D. He no longer allows friends who are promoters to book him without paying a deposit, so if they gamble on an event and end up cancelling it, he has some income guaranteed. “It’s got to that stage where you have to treat them like someone you don’t know, to make sure you get paid yourself. It can be awkward,” he admits. “But business is business innit. If it was the other way round, I’m sure they would do the same.”

The burden of a more business-like mindset is also damaging to the grassroots and diversity of dance music. This is something that the pandemic had actually improved: revelations from London to LA have celebrated the democratisation of space and attention during lockdown making a positive impact on post-lockdown underground scenes. You didn’t need a stash of capital to set up a live stream and share a link, for example, and audience attention was less strictly funneled through the filters of this popular venue, that dominant genre, or the influence of more complex, institutional power structures. Curiosity was piqued, tastes broadened, communities developed and new perspectives gained traction. Now that money is becoming a deciding factor again, this progress is at risk.

“You have to turn down some of the more DIY, independent projects, which is definitely impacting that scene,” says Ifeoluwa, who runs the Intervention workshops and events that aim to challenge hegemony in dance music. “Obviously structurally there’s less money going to those communities and projects, and now people have to start saying no because they can’t afford to work for free as much. You have to put your passion projects on the sideline.

“It was easier in the pandemic because it felt like you weren’t fighting to be in physical spaces, now we’re fighting to be in physical spaces with people who don’t want us to be there,” they add, noting the impact on marginalised communities. “Now to make money, people have to advertise what they know sells, and what sells is what is mainstream and what is palatable.”

Artists exploring niche sounds and the venues that rep them are more likely to struggle, which creates a vicious cycle inhibiting musical evolution. “It is often specialist music venues, catering to non-mainstream, niche audiences that invest heavily in talent and have lower profit margins as a result,” notes Tony Rigg. “Such privately owned independent businesses are often passion projects born out of a love for music. The value created by these cannot just be measured economically as their contributions are also cultural and enhance communities and wider society. Dancefloors are often where new electronic music is tested and incubated. They are a vital part of musical ecosystems in respect of talent development.”

A scene that stagnates is one that risks extinction. “I’m a bit worried about the new generation, because they won’t be able to hear [and be inspired by] so many different things,” comments Ifeoluwa. “We could end up just having this weird nostalgia repeat thing. A lot of nights are like fresher’s week 2012, but everyone’s 30. It’s really strange. Really, we should have had another ‘dubstep moment’, and just haven’t. I think underground music could be in danger in the next years.”

Touring internationally being more unaffordable also limits the spread of new sounds and ideas reaching new audiences, as well as hitting most artists’ primary income stream. DJs are at least fortunate in being able to travel light with a record bag or USB, and are relatively unaffected by the expensive and confusing post-Brexit rules that many bands and their bigger banks of equipment are dealing with between the UK and Europe. But that mess of paperwork and bureaucracy reflects the barriers DJs from outside EU nations – particularly non-Western, non-white – have always had to deal with when trying to secure touring visas. A proposed 250% price hike in visa fees for foreign artists touring in the US – from $460 (£385) to $1,615 (£1,352) – would make that market less accessible to any international DJ below a certain threshold of popularity or wealth, especially if the US dollar appreciates to 2022 levels again.

On a more microeconomic level, DJs operating independently are being hit by the rising cost of petrol and public transport. “I only ever travel on public transport when it is a requirement to travel for gigs. Public transport prices are increasing all the time!” says Kalli. “I use a railcard, which will run out soon as I’m 30 this year – it will be noticeably more when that expires.”

If you have a team, you’re better protected. “Travel expenses are never really a worry for most artists with an agent, because travel expenses are always covered by promoters,” says Parris. But it can still be difficult to lock down bookings. “I’ve had to turn down certain gigs because the cost of airfare makes it impossible to find a fee that allows both me and the promoter to be fairly compensated,” says San Francisco-based DJ Chrissy.

The artists being the worst hit are the ones living in smaller cities and poorly connected regions. “Travelling has been pretty difficult for me since the end of the pandemic,” says Belfast-based DJ Holly Lester. “If a flight is canceled here, chances are you won’t be able to get another one, so you then miss the gig. It’s always been pretty badly connected here, but now there are even fewer flights, collapsed airlines and increasingly expensive fares.”

Man Power, who’s based in the North East of England, observes similar issues. “The number of budget airlines and flights out of Newcastle has reduced dramatically,” he notes. Fewer routes limits the amount of places you can be booked or afford to go on tour, due to the cost of additional flights. “As a touring DJ outside of London, my costs are far higher, because it’s automatically an additional flight added on. That’s assuming we can still connect at a decent sized hub like [Amsterdam] Schipol, [London] Heathrow or Frankfurt. In a lot of cases, it’s an extra two flights added onto the itinerary now, simply because the routes have reduced so dramatically,” says Man Power.

“Promoters understandably are trying to keep their costs down in the UK, so when it comes to choosing between me and say, an artist based in London, they are going to go with the latter,” says Holly Lester. “It’s something that I’m dealing with continually and then I’m asking myself: ‘Am I in the right place?’, but the reality is I can’t afford to leave Belfast.” Kalli recently moved out of London to a place near Brighton, attracted by the more affordable rent. “I was aware I might not be able to build up an artist career like I maybe could have done in London,” he says.

Artists living outside of major cities in the UK are already at a disadvantage when it comes to gaining popularity and bookings – and generally surviving as an artist – and now it’s getting even more difficult.

“The North East of England has been having a cost of living crisis since the 1960s. This is just the latest phase of a similar problem that happens for everybody in this region, and other regions with a similar profile,” says Man Power. “As such, we’re gonna see a real drain on artists from impoverished areas, because they simply can’t afford to be an artist. The amount of artists who I’ve spoken to who were eking out a relatively reasonable career in the North East pre-pandemic and cost of living crisis, who have now had to turn towards full-time work… I know people who have gone onto working in call centres, other people have gone onto working offshore, for the oil and gas industry, which is a story as old as time for people in the North East.

“It used to be the case that you got one chance to try and make something work, and if it didn’t you were screwed. Now it’s getting to the point where people don’t even have that initial chance.”

When support is available, the benefits are material. One of the biggest success stories in post-lockdown UK dance music is North East-hailing hard house DJ and producer Shakeil Luciano AKA Schak. In October 2022, he was on the dole and struggling to get by. Then his high-energy track ‘Moving All Around (Jumpin’)’, which features Kim English, was released via Trick and Ministry Of Sound, and his popularity soared. “I was struggling to pay me rent and having to think about if I can buy groceries,” he recalls. “Now I’m making daft money. It’s completely changed my life. At the end of the year I might be able to buy me mam a house.”

Alongside his mum, two people played a significant role in this success. One is Trick label boss Patrick Topping, one of the UK’s biggest DJs whose resources and popularity gave a platform to Schak. “He changed me life,” says Schak. Another is an employee of the Department for Work and Pensions, who allowed Schak to spend the 36 weekly hours of job search, required to receive Universal Credit, focusing on his music. “He’s a fellow music artist so he understood the pain and the strife it takes to become successful,” says Schak. “Without him I would never, ever be where I am. I owe so much to him.”

At 30-years-old, it’s his debut release, and currently has more than 15 million streams across Spotify and YouTube. It’s a heart-warming chapter of a story with a gloomier background. “I’ve been through some dark times,” Schak says. When – eventually – given the opportunity, his talent translated into success. But there are many talented amateur musicians out there who don’t get that chance: who aren’t from a supportive family, whose income isn’t managed by a sympathetic public servant, who don’t catch the attention of an influential DJ who cares about their local scene. “The thing about being a DJ and what we do is, there’s a degree of it that is luck,” notes Parris. “You work hard, but there is also a degree of luck, there’s also a degree of things connecting at the right time and the right place.”

To enable more talented musicians to flourish, proper support structures need to be funded and developed at scale. “We need to build infrastructure,” says Man Power. “I would like to see money being given to grassroots organisations to support people regionally in developing their own voices, in a way that’s authentic to the region that they come from.”

That money could come from state funding, community fundraisers, and donations — institutions that profit heavily from the talents that do emerge to stardom, such as major labels, mega venues and even superstars themselves, should be expected to contribute. “There’s aspects of the music industry that are doing very well,” says Matt Griffiths, CEO of charity Youth Music. “It’s a win-win if you invest in the grassroots. Because you’re doing something good, you’re protecting the music industry and education infrastructure. But you’re also supporting the future talent pipeline.” Even the top of the industry won’t survive if the bottom falls out. “It’s important to amplify DIY promoters and grassroots venues and understand the specifics of the local scenes outside of London,” says VAJ.Power. “We are living in a symbiosis, and need to help each other grow.”

Money from brands is also an option, and a funding source that’s increasingly hard to avoid for every creative industry trying to stay afloat in late capitalism. But even the biggest advertisers are slashing marketing budgets amid recession fears. And when stumping up, there are valid concerns that this money strengthens the capitalist chokehold on creativity, and that commercialisation goes against the foundational values of dance music.

Powerful individuals are more often a problem than a solution, but unselfish individuals can help make a difference on some level. That’s something Chrissy calls for: “Don’t be the rich kid who hires an army of publicists and managers to build you a career from scratch; instead be the rich kid who starts a label or nightclub and hires an army of publicists and managers to build careers for you AND a diverse crew of other talented artists who didn’t have your same luck.” After breaking through, Schak is now thinking about ways he can give back. “One day I want to build a mental health charity foundation to help others because they get fuck all from the government. I want to build a community centre where kids can go for additional support, harness their skills and get educated properly about life.” Beyond funding, individuals can provide support with volunteering and skill-sharing.

Arts funding and social support structures can be a lifeline for musicians, and organisations such as Arts Council England, PRS Foundation, Help Musicians, Youth Music, and more, offer crucial help in the UK that warrants more investment to improve the scope of their support.

“We’re having to say no to an increased number of applications – around 77%, which means we can say yes to 23%. We could double or treble that if we can raise more money,” says Youth Music’s Matt Griffiths. “We invest in a significant grassroots structure across the UK of about 500 organisations. 84% of our money is outside London. We look very carefully at the situation for each region.”

As it stands, there is not enough funding or niche expertise in the third sector to adequately meet demand. The administering of funds also lacks accountability, with accusations of gender and racial bias common. Who did and didn’t benefit from the UK government’s £1.57 billion Cultural Recovery Fund, distributed with help from Arts Council England, was a recent subject of controversy in dance music.

The likes of Metallic Inc’s Metallic Fund (for Black British creatives) and PRS Foundation’s Women Make Music fund (for women, trans and non-binary artists) are existing efforts to redress imbalances. More organisations and funds focused specifically on supporting dance music and artists from marginalised communities are needed. Along with more support for existing community-based platforms and non-profit organisations that have been set up in response to the failures of current systems.

Supa D, a linchpin of the Afro house underground, has not been successful when making grant applications. “They can pick and choose what sectors they want to do stuff for,” he says. Man Power has received multiple funding grants, but only for projects outside of dance music, such as writing a symphony for a collaboration with a classical orchestra. “I was supported if I wanted to stop being a DJ and if I wanted to move on into becoming something that these organisations can recognise as an artist, a composer,” he says.

Some artists feel the processes lack clarity. “I am an immigrant and I don’t have much access to public funds,” says VAJ.Power. “It’s a grey area that I didn’t want to meddle with as the visa requirements are quite vague on what government support is and what can be perceived as taking advantage of it. I erred on the side of caution there and passed on a few opportunities that the Scottish Government had available.”

Clemency has similar feelings. “I always feel like I’m in a grey area to take it cos I do have a day job. I definitely feel like it could be broadcast better, I barely know what’s available,” she says.

Advice employees of these funding organisations offer to musicians includes checking out the tips and guidelines on their websites, which are available in a variety of formats, providing specific details on how the funding would make a difference to yourself and your career, requesting assistance from them where needed, and making use of their pre-deadline advice sessions.

Arts Council England runs regular advice webinars and has a contactable Customer Service team, who can arrange help for people struggling to make applications due to disability or neurodiversity. Help Musicians runs ‘Get Set Sessions’, where musicians can learn about funding opportunities and get tips for making applications. PRS Foundation has videos, webinars and In Conversations with previous grantees on its YouTube channel to provide tips, advice and things to think about when applying. Youth Music doesn’t require lengthy forms, allowing video applications and short write-ups about creative visions as part of a process it calls Inclusive Grant Maintance focused on improving accessibility. “We’re conscious we’re in a position of quite a lot of power. We hold quite a lot of money so we make sure it’s distributed equitably,” says Griffiths.

“Don’t be put off if the first time you don’t succeed. Most funds allow you to apply again after receiving some feedback,” says a spokesperson for Arts Council England.

British DJ Mina has started up a service called Funding with Mina, assisting creatives with funding applications in the UK. “My advice would be to pretty much constantly be working on applications, the more you do the easier it gets,” she says.

Mina would also like to see “more funds open up for collaborative projects with artists outside of the UK” to create more opportunities for artists from the Global South. Musicians who aren’t from wealthy, Western countries rarely have access to arts funding. “In Uruguay? I wish! I never received any government funding back home,” says experimental artist Lila Tirando a Violeta, who recently relocated to Europe (“even though I profoundly love living in South America”) because it was proving impossible to earn a living as a musician there, 10 years on from her debut release.

The squeeze on artists who don’t make or play music palatable to mainstream tastes, and don’t rake in royalties or lucrative club and festival bookings, is further restricting who can access and operate within the industry. “I can’t really afford to have a radio show monthly now, as I want to exclusively play recent releases in my shows and I can’t afford to buy so much new music monthly,” says VAJ.Power. “I’ve also been wanting to get into producing for ages, but due to the amount of work I have to do [with my day job] I simply don’t have time.” Ifeoluwa also feels their creativity is inhibited. “Being neurodivergent, I’m very hands on, so I feel like I want to get bits of kit to go to the next level, but I can’t afford that. So it limits my creativity and makes me think, actually it’s not sustainable,” they say. “If I can’t make anything new I’m struggling to survive. I might as well just get a boring office job with the other skills I have. At least I know I’ll be able to eat next month, rather than always panicking.”

The changing of nightlife habits is a parallel problem, entrenching an upper class of headline DJs whose fees are only going up while other artists are left to struggle. Keep Hush’s U Going Out? Survey found people are now going out less regularly but ‘cheap tickets’ was ranked as the least important factor when deciding what to attend, indicating people are willing to spend if they think they’re getting their money’s worth. Single concert tickets for popstars now tend to cost triple-figure sums and their stadium shows sell out. In dance music, this is being mirrored by the rise of huge, festival-style nightclubs with bulging line-ups and expensive production.

“You have super venues who are gigantic, with super artists who can command gigantic fees. They’ve gone up. They’ve sucked up all of the crowds, and all that means all of that money is going into the hands of a small number of people,” says Man Power. “The money available for people who aren’t super big headliners or headliner-adjacent is reducing [while the cost of living is getting more expensive]. You’re getting burnt at both ends.”

The popularity of these events – which are often day parties – is disrupting the very notion of nightlife in major cities (though this may be a symptom not a cause of consumer habits changing). “In the next few years in London, I think you’ll basically all be going to pre-midnight parties, pre-11:PM watersheds, because night-time parties are just losing more and more. I’ve got to adapt my brand and introduce that slowly; do more day parties,” says London-based DJ and promoter Shenin Amara, who makes most of his income throwing events, including the long-running House Passion and The Asylum series. “We’re in a place where the night parties are the after parties for all of these Printworks, Tobacco Docks [type events]. That’s more or less where we’re at now.”

Generational differences may be at play here, with alcohol consumption falling among Gen Z, and restaurants, shisha bars, late-night dessert parlours and even things like escape rooms increasingly filling the space that pubs, bars and clubs have done previously. Chrissy considers that “perhaps … clubs have failed to make themselves safe, attractive, interesting spaces for Gen Z to come spend their money”. A 2023 report from the Night Time Industries Association (NTIA) found that electronic music is the most popular genre at UK festivals, and the second most popular genre in the UK, while the number of nightclubs is in freefall.

The boom of ‘90s rave nostalgia among Gen Z, which has been linked to the struggling economy and developed on TikTok not dancefloors, is an indicator of how trends go without a nightlife infrastructure. Finding ways to boost diverse, DIY nightlife and the nightclub industry – where new genres and movements are often developed – is fundamental to the health of dance music.

“I just feel like, in a few years, we’re going to be so limited,” Shenin says, commenting on the reduction of spaces available for diverse strands of nightlife to operate. “There’s less venues for us to put tech-house events in, it’s the same if you’re a reggaeton promoter or drum ‘n’ bass or whatnot.” Amara has been active in the London scene for nearly two decades, and previous periods of economic hardship have not proven so challenging. “When I did house events in the 2008/9 recession times, that was one of my greatest times for events,” he reveals. Parris says there was no economic impact from a punters’ perspective. “When I first started going out in 2009, I used to go to FWD>> every week and it was a fiver. £5 and a bus ride home, every night was £7. I could do that every week!” he says. Tickets for the recent FWD>> comeback event – a festival-style day party at Printworks (with an official after-party at The Cause) – were priced from £24.50 up to £39.50 (plus fees).

Shenin has taken to tapping into the sentimental raver market to boost revenues, launching his Back To 2012 night in 2018. “It’s very nostalgic, it’s about that 2010-2014 era of deep house,” he says. It’s proven popular, packing out 1000+ capacity venues, but only works on an irregular schedule and isn’t fertile ground for sustainability. “That crowd, the older crowd I’m going for, they don’t go out so much,” he says. Attracting new generations of fans and artists is necessary for the survival of nightlife, and as it stands, people are going out less and dance music is a less viable career path.

These struggles follow the pandemic already pushing out many musicians or placing limitations on new artists being able to establish themselves. “This latest economic downturn has derailed the careers of a lot of people who had sustainable practices making music and gigging at a level that allowed them to pay the bills, enjoy their life, and exist at a level they wanted to,” says Man Power. “If you have to take a job out of necessity and you’re caught in that grind, a lot of times that’s you for the rest of your life, especially if you’re not in your early 20s.” This is a worry for VAJ.Power: “I hit my mid-20s just as lockdown happened and I missed out on a lot of opportunities because of this,” they say. “I’m mostly concerned that I lost my chance and with the amount of work I have now, investing into my creative outlets became something I can’t afford to be so proactive with.”

Even for relatively established artists, rising costs such as the expense and overdemand of the vinyl industry are causing problems. While big labels with high volume orders can cut deals and jump queues, independent artists have higher prices and longer waits which can stunt career growth. “I think I get booked more for my productions than DJing at the moment, so it’s important I have records out,” says Parris, noting his 2022 schedule, following the release of his debut album, was busier than how 2023 is shaping up. “Can I really be sitting here waiting six months for a record to be pressed? You’re delaying parts of your career and losing steam, over a piece of wax!”

Holly Lester, who runs the Duality Trax label, is also feeling the strain. “I’m still dealing with the impact of the pandemic financially, and now also dealing with inflation, huge energy bills. I’m also seeing massive increases in manufacturing costs for my record label, so overall it’s becoming pretty stressful,” she says. Wisdom Teeth co-founder Facta thinks this could spell the end of club records: “I think most indie dance labels will stop doing them entirely by end of year and only press LPs. Say goodbye to club 12″s” he tweeted in February.

Most musicians, even ‘full-time’ ones, need diversified income streams to survive. “The entire music industry relies on the unpaid or underpaid labour of musicians and other creatives to function,” says Chrissy. “People who already have a ton of money might be able to focus on their art without taking on a bunch of musical odd jobs, but the rest of us have been wearing multiple hats since the beginning. The system has been untenable for years, and the cost of living crisis has merely made the issue more visible.”

Within music, options include ensuring you’re registered with royalties services like PRS, MCPS and PPL; curating; teaching; licensing your music for use in adverts, films, games; and taking briefs from brands. But as with any freelance employment, there’s a lack of security. “There’s very flaky companies. They can offer a large amount of money, but you can’t really put a guarantee on them,” says Parris “Something you could have been relying on can get taken from you; people just change their mind, and you just can’t do anything about it. When you’re in a situation like the cost of living crisis, it’s quite hard to see a silver lining coming through, only for it to get closed again.” Money management, unglamorous thought it may be, is an important skill.

The lack of stability can be “incredibly stressful”, as Chrissy puts it, and damaging to artists’ mental health. Sarah Woods, Deputy Chief Executive of Help Musicians, reveals calls to Music Minds Matter, the UK charity’s dedicated mental health helpline for people working in music, have gone up 200% over the past two years, and last year requests for therapeutic support rose by 35%.

Increasingly, musicians are having to look beyond music for stability. “At the moment I’m thinking of doing a van hire company,” reveals Supa D. DJ S says he managed through the pandemic because he’s “made shrewd investments” in properties, while the government grants he got relating to his popular Pure Silk and House Of Silk parties he calls “a bit of a joke”, amounting to around “4 or 5%” of what he could have been making, well below the 80% rate for furloughed company employees.

Hailing from a country with inadequate public services also makes being a musician more risky. “I suffer from very complicated health issues and in all honesty my main concern is that I don’t get any insurance,” says Lila Tirando a Violeta.

Kalli names a concern as “some labels, agents and other entities not having an empathetic approach to their clients and musicians, in a time of economic crisis. There doesn’t seem to be a Human Resources team for working artists, it is all self-employed work unless you work for corporate organisations.” Charities pick up some of the slack. As well as Music Minds Matter, Help Musicians provides crisis support relating to retirement, illness, injury, bullying and harassment.

“It would be nice to see larger agencies offer things like mental health support or crisis support to artists in 2023,” considers Holly Lester. “It’s really important that artists who are struggling don’t feel like they are alone in this situation, or any other challenging situation.”

“Talk to your friends and peers – sounds obvious – but we’re largely in the same boat,” advises Clemency. “Be there for your fellow artists,” encourages Kalli. “Communities are important in the creative universe.” In a yellow square wisdom drop, Elijah advocates teamwork: “Nobody is self made”.

Finding cooperative ways of working to navigate the tricky economic times has become vital for sustaining underground scenes. “Being on both sides as a DJ and a promoter, I think we need to work together and not against each other in such difficult circumstances,” says VAJ.Power. Parris backs this approach. “I’m reasonable,” he says. “Yes, it’s nice to have a higher booking fee because it sorts me out a lot better, makes me less worried. But I’m not a demon, I don’t have a minimum. If a party is going to be good, I’m happy to do it for what works for everyone: promoter, agent and me.” Kalli, who fits DJing around a mentally exhausting office job and the demands of raising a young family, keeps the music at the forefront of his mind. “My booking fees will depend on what the promoter can afford. I try to be flexible for all gigs; if I’m trying to promote my music or support a specific sound I’m obsessed with, I would do what I can to make it happen.”

A community-focused mindset has been core to dance music since its origins in Black, Latin and queer communities, who came together in the face of oppressive conditions and built a culture that has become a global phenomenon. Not holding those values as core moving forward is a betrayal of those roots. But not only that, it’s necessary to survive the oppressive conditions of today.

That goes for the dance music industry as a whole. This article has explored issues within nightlife through the lens of artists, but it’s apparent that the issues run deep and relate to the whole ecosystem. There’s no doubt that some of the people best protected in nightlife are artists: ones who can command exorbitant fees and partnerships. No festival headline-level DJ returned a response for comment for this article, and for now they are unaffected. In a 2021 essay, Mathys Rennela makes the case to Abolish DJ Idolatry for a more equitable music industry, arguing in favour of centring the perspective of club workers as the industry archetype. Tony Rigg makes the case for collective action from across the industry: “We need to continue amplifying our collective voices to inform policy makers about the substantial contribution these sectors make to economy, culture and society, in order to be pushed up the pile. The sector also needs to continue being creative and innovative in finding ways to overcome these challenges, as it always has done.”

The main issue when it comes to artists is accessibility. Recent findings of the IMS 2023 Business Report revealed that just 20% of creators make a living from dance music, despite the industry growing by 34% in 2022. If dance music continues on this trajectory, with domineering artists and institutions hoovering up all the resources, it will only be accessible to the privileged, and become a preserve of the rich like modern art. This doesn’t make for an interesting, diverse and dynamic scene, befitting of its historical ties to activism and social revolution.

“Sadly I feel like we will come away from this with a massive loss of talent and a career in dance music will become even more unattainable to anyone without considerable financial backing,” reflects Holly Lester, which is happening across the arts.

In our 2017 interview, Paula Temple considered an alternative. “My absolute desire is for the money system to collapse. There are better systems that have been well thought out and are on offer, it’s just that our minds and resources are still controlled. This is in direct conflict with a lot of the beliefs that artists like myself and scenes like the underground techno scene hold.”

And with our current systems not fit for purpose, why not consider radical solutions? “We live in a completely new world now, so it’s a constant figuring out things as we go,” reflects VAJ.Power.

Currently, boom and bust cycles are tied into our way of living. The challenges against the dance music industry are great, but the dance music culture it came from will always be there. It’s shown itself to be a hotbed of creativity and a compelling antidote to societal norms, filled with grassroots passion, innovative minds and communal experiences that change lives. The diversity and values which make dance music great need to be supported so they’re still there coming out the other side. Inequality has always been rife in society — dance music should represent a counterculture and not a mirror.

“If you are creative and you have this compulsion, just hold tight,” urges Man Power. “It will be harder for a long time, and it might be cold baked beans for a little bit, but ultimately in my experience it’s worth it, to take part in an enriching and satisfying way of living. I’ve seen it get better before and it will get better again.”

mindvault

14 October 2025 at 19:14**mindvault**

mindvault is a premium cognitive support formula created for adults 45+. It’s thoughtfully designed to help maintain clear thinking

prostadine

20 October 2025 at 08:09**prostadine**

prostadine is a next-generation prostate support formula designed to help maintain, restore, and enhance optimal male prostate performance.

sugarmute

20 October 2025 at 15:31**sugarmute**

sugarmute is a science-guided nutritional supplement created to help maintain balanced blood sugar while supporting steady energy and mental clarity.

gl pro

21 October 2025 at 00:39**gl pro**

gl pro is a natural dietary supplement designed to promote balanced blood sugar levels and curb sugar cravings.

vittaburn

21 October 2025 at 11:50**vittaburn**

vittaburn is a liquid dietary supplement formulated to support healthy weight reduction by increasing metabolic rate, reducing hunger, and promoting fat loss.

mitolyn

21 October 2025 at 11:56**mitolyn**

mitolyn a nature-inspired supplement crafted to elevate metabolic activity and support sustainable weight management.

prodentim

21 October 2025 at 12:00**prodentim**

prodentim an advanced probiotic formulation designed to support exceptional oral hygiene while fortifying teeth and gums.

synaptigen

21 October 2025 at 12:52**synaptigen**

synaptigen is a next-generation brain support supplement that blends natural nootropics, adaptogens

zencortex

21 October 2025 at 12:53**zencortex**

zencortex contains only the natural ingredients that are effective in supporting incredible hearing naturally.

yusleep

21 October 2025 at 13:25**yusleep**

yusleep is a gentle, nano-enhanced nightly blend designed to help you drift off quickly, stay asleep longer, and wake feeling clear.

nitric boost

21 October 2025 at 13:46**nitric boost**

nitric boost is a dietary formula crafted to enhance vitality and promote overall well-being.

glucore

21 October 2025 at 14:19**glucore**

glucore is a nutritional supplement that is given to patients daily to assist in maintaining healthy blood sugar and metabolic rates.

wildgut

21 October 2025 at 14:44**wildgut**

wildgutis a precision-crafted nutritional blend designed to nurture your dog’s digestive tract.

breathe

22 October 2025 at 04:34**breathe**

breathe is a plant-powered tincture crafted to promote lung performance and enhance your breathing quality.

energeia

22 October 2025 at 12:05**energeia**

energeia is the first and only recipe that targets the root cause of stubborn belly fat and Deadly visceral fat.

boostaro

22 October 2025 at 12:37**boostaro**

boostaro is a specially crafted dietary supplement for men who want to elevate their overall health and vitality.

pinealxt

22 October 2025 at 12:40**pinealxt**

pinealxt is a revolutionary supplement that promotes proper pineal gland function and energy levels to support healthy body function.

prostabliss

22 October 2025 at 12:44**prostabliss**

prostabliss is a carefully developed dietary formula aimed at nurturing prostate vitality and improving urinary comfort.

potentstream

22 October 2025 at 21:22**potentstream**

potentstream is engineered to promote prostate well-being by counteracting the residue that can build up from hard-water minerals within the urinary tract.

hepato burn

23 October 2025 at 09:07**hepato burn**

hepato burn is a premium nutritional formula designed to enhance liver function, boost metabolism, and support natural fat breakdown.

hepatoburn

23 October 2025 at 13:48**hepatoburn**

hepatoburn is a potent, plant-based formula created to promote optimal liver performance and naturally stimulate fat-burning mechanisms.

cellufend

23 October 2025 at 22:28**cellufend**

cellufend is a natural supplement developed to support balanced blood sugar levels through a blend of botanical extracts and essential nutrients.

prodentim

24 October 2025 at 00:03**prodentim**

prodentim is a forward-thinking oral wellness blend crafted to nurture and maintain a balanced mouth microbiome.

flow force max

24 October 2025 at 00:11**flow force max**

flow force max delivers a forward-thinking, plant-focused way to support prostate health—while also helping maintain everyday energy, libido, and overall vitality.

revitag

24 October 2025 at 00:54**revitag**

revitag is a daily skin-support formula created to promote a healthy complexion and visibly diminish the appearance of skin tags.

neuro genica

24 October 2025 at 02:41**neuro genica**

neuro genica is a dietary supplement formulated to support nerve health and ease discomfort associated with neuropathy.

sleeplean

25 October 2025 at 01:18**sleeplean**

sleeplean is a US-trusted, naturally focused nighttime support formula that helps your body burn fat while you rest.

memory lift

26 October 2025 at 12:19**memory lift**

memory lift is an innovative dietary formula designed to naturally nurture brain wellness and sharpen cognitive performance.

fk88betvn

3 December 2025 at 07:16Alright, folks! Just checked out fk88betvn. Seems like a decent spot to try your luck. Give it a whirl and see what you think! Check it out here: fk88betvn!

55lotterybet

3 December 2025 at 13:14Just put a few bucks on 55lotterybet. It’s pretty straightforward to use. Let’s see if I can snag a win! Fingers crossed! Place your bets: 55lotterybet